Your Tax Dollars and Those Pesky Key Indicators

May 13, 2015

In a Washington Post op-ed piece yesterday, Catherine Rampell takes on presidential candidates pledging to “run government like a business,” as they advocate inane policies like 10% across-the-board cutbacks. Rampell argues that like real businesses, “sometimes you have to spend money to make money,” and cites some excellent examples.

I take a slightly different perspective. Businesses don’t maximize profit by spending money to make money, they set goals – which may require money to be spent. Goals that can be measured. And then they keep score. Key to this process is identifying the right metrics, or key indicators, or OKRs, or targets, or what most of them really are: plain old ratios. Ratios like:

- Revenue growth

- Profit margin

- Revenue per headcount

- Expenses per headcount

- Return on investment (typically used to evaluate individual projects)

- Average customer satisfaction score

The problem isn’t that the federal government doesn’t spend money to make more money, it’s that they don’t use the appropriate metrics when planning and when evaluating themselves. Using metrics is critical in an institution like the federal government, where the raw numbers are so huge that they defy comprehension by most normal humans.

The Internal Revenue Service is one example Rampell cites. In 2013, they collected $256 for every $1 they spent. And yet, their budget has been getting cut for years while their responsibilities have expanded – most significantly, they are the calculation and enforcement agency for the Affordable Care Act subsidies. Are Congress and the OMB thinking of the right metrics when they cut the IRS budget? Ditto for IRS management, when they devote dollars to providing service to honest taxpayers, or to anything else other than auditing and enforcement capabilities? (As an honest taxpayer myself, I cringe as I write these words.)

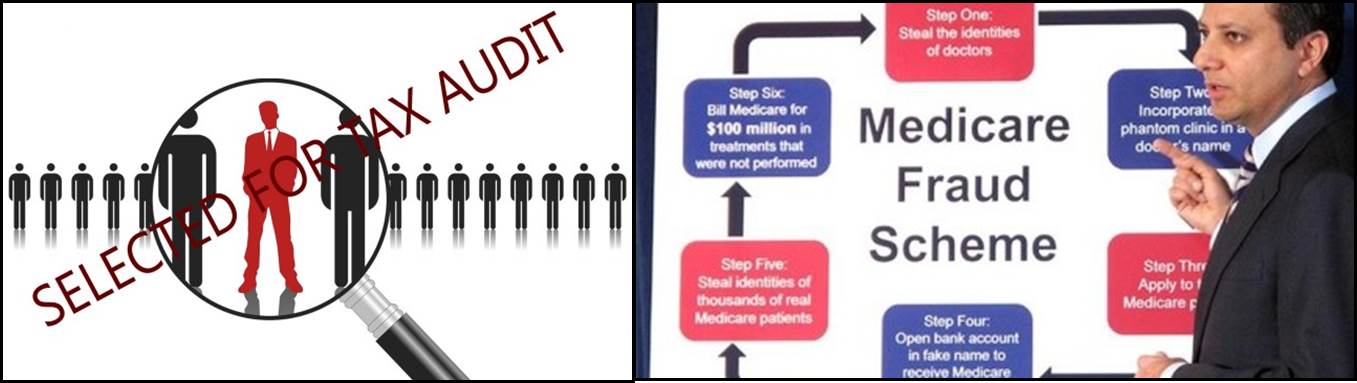

Another example is Medicare/Medicaid, where estimates of spending on fraudulent claims run as high as 10% of total HHS spending, or more. Here are some metrics:

- Collection efforts against fraudulent claims recover about $8 for every $1 spent (per The Economist). Moreover, amounts recovered may also act as a deterrent against future efforts to commit fraud.

- Fraud losses sustained by private sector insurers are closer to 1%-1.5% (per Forbes). Fraud estimates may be imprecise, but this difference between the private sector and Medicare/Medicaid can’t be ignored. What accounts for the difference?

Every organization – a business, a school, the federal government, your family – functions better when it’s keeping score, using metrics that actually make sense. What are your favorite key indicators?

“Painting with Numbers” is my effort to get people to focus on making numbers understandable. I welcome your feedback and your favorite examples. Follow me on twitter at @RandallBolten.Other Topics